Orientalism, according to Edward W. Said, is a discourse. One in which words, concepts, ideas and termsare constantly allowed to intermarry with one another, with the ardent purpose of producing one narrative. The singularity of this narrative, in turn, becomes a monopoly of knowledge. A monopoly, that is further supported by a vast army of scholars, thinkers, think-tanks, and government authorities. All with the aim to “reproduce” the region or the world, in the image with which it was first found; orperceived to have been found. Orientalism, for lack of a better word, is another culture imposing its views and values on the other; only to allow it to grow, prosper, and flourish with time.

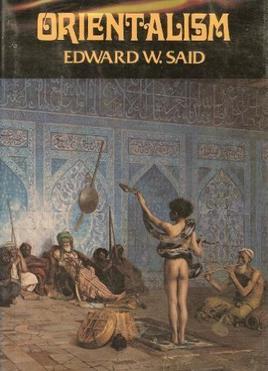

For example, it has been close to half a millennium that the Arabs have been described as a people driven by perpetual lust and debauchery. The idea remains as poignant today as it was five hundred years ago. Yet, “Orientalism,” as written by Edward W. Said in 1977, also argued that each idea or concept is fluid. With time, what seems stable will also undergo dramatic change. Nothing stays the same. Even Islam, a religion that is based on the concept of Tawhid, the one-ness of God, is subject to impressive interpretations and intellectual combats.

Some argue that the one-ness of God presupposes the creation of a totalitarian theocratic state. Others argue that the one-ness of God must be open to permissive interpretation by all sides, granted the Quranic verse that “to each their religions.” What is one and many? What is many and one? Orientalism, contrary to the belief that it is merely a tract that seeks to underscore the Western domination of the “East,” speaks of the very fluidity of the concept; indeed any concept. Even “America,” was reclaimed by the American rightwing with the election of President Trump. Everything that is contestable will be re-contested. “Orientalism,” harks at this divisive idea more than anything else. All things are never the same.

However, granted the interpolation of Western foreign policy in “Orientalism,” this book is also read as a vindictive condemnation of all that is wrong with the West; including the tendency of the West to dominate others. While the West has indeed colonized close to 85 percent of the world’s entire surface in the 19th century, the West has also relinquished its control.

Nowhere has there been a greater attempt to unhinge oneself from the other. “Orientalism,” hints at both and all possibilities. But to a great many who read it, it is regarded as a Bible of anti-Westernism; when in fact it never was. Therein, lies the peculiar paradox and legacy of the late Edward W. Said, who was a well-known pianist and humanist.